de Thulstrup, Thure. Battle of Shiloh. (1888).

T

|

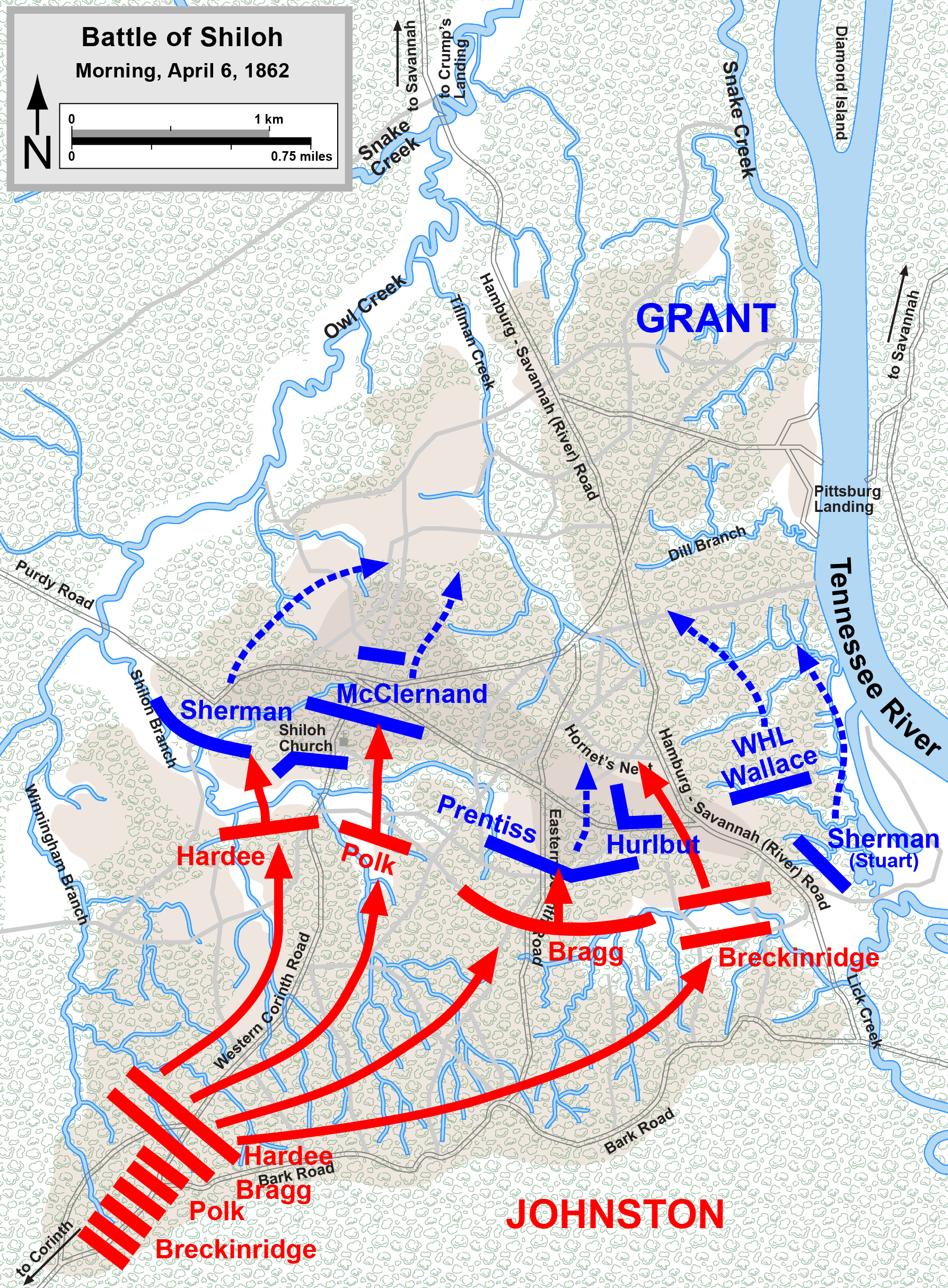

Battle of Shiloh, April 6, 1862

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shiloh_Battle_Apr6am-2.png

Ambrose Bierce, circa 1866(?)

In 1881, nineteen years after the battle, Bierce published “What I Saw at Shiloh,” in the San Francisco newspaper, The Wasp. Its first lines declare both his object and limitations, as well as those of the audience: “This is a simple story of a battle; such a tale as may be told by a soldier who is no writer to a reader who is no soldier.”[1] Despite this caveat, Bierce was by then a well-regarded writer as well as an accomplished soldier. He was especially renowned as a topographer, and his memoirs on Shiloh reflect his careful analysis of the terrain of the battle. But unlike many of his fellow author-veterans, who by the 1870s were publishing their purportedly heroic exploits from the war, Bierce repeatedly sought to puncture the myth of war as noble, gallant, or heroic. Many of his short stories were set against the backdrop of the Civil War, where he frequently explored the disconnect, madness, and horror experienced by individual soldiers. In the case of “What I Saw at Shiloh,” we have a rare example of a non-fictional treatment of his war experience, very likely published as a corrective to his more glory-seeking contemporaries.

Shiloh National Military Park

Bierce describes looking upon the scene at Shiloh early on the morning of April 7th: “Presently the flag hanging limp and lifeless at headquarters was seen to lift itself spiritedly from the staff. At the same instant was heard a dull, distant sound like the heavy breathing of some great animal below the horizon. The flag had lifted its head to listen.” However, there is no alluring metaphor or sentiment to cloak what Bierce and his regiment witnessed as it passed through where the Union army had retreated. Bierce recalled that:

[Grant’s men] were mostly unarmed; many were wounded; some dead…Not one of them knew where his regiment was, nor if he had a regiment. Many had not. These men were defeated, beaten, cowed. They were deaf to duty and dead to shame. A more demented crew never drifted to the rear of broken battalions. They would have stood in their tracks and been shot down to a man by a provost-marshal's guard, but they could not have been urged up that bank. An army's bravest men are its cowards. The death which they would not meet at the hands of the enemy they will meet at the hands of their officers, with never a flinching.

Bierce also takes a moment to observe the juxtaposition of Shiloh Church: “The fact of a Christian church…giving name to a wholesale cutting of Christian throats by Christian hands need not be dwelt on here; the frequency of its recurrence in the history of our species has somewhat abated the moral interest that would otherwise attach to it.” It was in this same spirit of cynicism that Bierce would relate the gore—rather than the glory—that the battlefield rendered. Upon viewing a wounded Union soldier, Bierce reported on the scene with a brutal honesty that was jarringly un-Victorian: “A bullet had clipped a groove in [the soldier’s] skull, above the temple; from this the brain protruded in bosses, dropping off in flakes and strings. I had not previously known one could get on, even in this unsatisfactory fashion, with so little brain.” Bierce’s black humor is what gave him notoriety and success as a journalist, but this was not the fashion in which most veterans chose to publicly recount the suffering of their fellow soldiers.

But topography, gore, and cynicism were not all that Bierce recalled of his complicated experiences at this battle. In the most tender reflection of “What I Saw at Shiloh,” Bierce laments what a cruel burden of war the survivors had to endure: the obliteration of youth and the gruesome legacy of war. The concluding passage features some of most elegiac prose written about the war:

Without illusion to the war’s causes or consequences, and without deference to honor, valor, or freedom, lies a simple story of a battle told by a soldier. That soldier became a writer who helped contextualize for his readers what was won and lost by one man at Shiloh in the spring of 1862.

_____________________________

Bierce also takes a moment to observe the juxtaposition of Shiloh Church: “The fact of a Christian church…giving name to a wholesale cutting of Christian throats by Christian hands need not be dwelt on here; the frequency of its recurrence in the history of our species has somewhat abated the moral interest that would otherwise attach to it.” It was in this same spirit of cynicism that Bierce would relate the gore—rather than the glory—that the battlefield rendered. Upon viewing a wounded Union soldier, Bierce reported on the scene with a brutal honesty that was jarringly un-Victorian: “A bullet had clipped a groove in [the soldier’s] skull, above the temple; from this the brain protruded in bosses, dropping off in flakes and strings. I had not previously known one could get on, even in this unsatisfactory fashion, with so little brain.” Bierce’s black humor is what gave him notoriety and success as a journalist, but this was not the fashion in which most veterans chose to publicly recount the suffering of their fellow soldiers.

| Tennessee War Memorial at Shiloh National Park Source: http://www.civilwar.org/photos/galleries/shiloh/tennessee-monument-at-jones.jpg |

The Union Army by the end of the following day had taken back Grant’s original camp position, driving the Confederate Army from the field, where it retreated to Corinth. Much like the Confederates the day before, the Union army was unable to follow up on its victory due to the high cost paid on the field. In these two days of battle, there were an unheard of 24,000 casualties, at the time the most in American history, only to be eclipsed several times in other battles as the war dragged on. Despite these horrific numbers, the grim carnage of death was often subdued or omitted entirely in memoirs of the war, which instead tended to highlight the heroism and valor demonstrated by soldiers of both armies for the all-American goal of “freedom.” This played into a larger spirit of reconciliation between white Americans, especially after the end of Reconstruction in the South. Bierce had no qualms breaking from that convention in relating the gruesome nature of battle without the pretense of justification or rationalization. As he surveyed the aftermath of the crimson landscape of Shiloh, he depicted this grisly scene: “[The soldiers’] faces were bloated and black or yellow and shrunken. The contraction of muscles which had given them claws for hands had cursed each countenance with a hideous grin. Faugh! I cannot catalogue the charms of these gallant gentlemen who had got what they enlisted for.” The rage militaire of 1861-1862 found its punctuation at Shiloh.

But topography, gore, and cynicism were not all that Bierce recalled of his complicated experiences at this battle. In the most tender reflection of “What I Saw at Shiloh,” Bierce laments what a cruel burden of war the survivors had to endure: the obliteration of youth and the gruesome legacy of war. The concluding passage features some of most elegiac prose written about the war:

O days when all the world was beautiful and strange; when unfamiliar constellations burned in the Southern midnights, and the mocking-bird poured out his heart in the moon-gilded magnolia; when there was something new under a new sun; will your fine, far memories ever cease to lay contrasting pictures athwart the harsher features of this later world, accentuating the ugliness of the longer and tamer life? Is it not strange that the phantoms of a blood-stained period have so airy a grace and look with so tender eyes? - that I recall with difficulty the danger and death and horrors of the time, and without effort all that was gracious and picturesque? Ah, Youth, there is no such wizard as thou! Give me but one touch of thine artist hand upon the dull canvas of the Present; gild for but one moment the drear and somber scenes of to-day, and I will willingly surrender another life than the one that I should have thrown away at Shiloh.

Without illusion to the war’s causes or consequences, and without deference to honor, valor, or freedom, lies a simple story of a battle told by a soldier. That soldier became a writer who helped contextualize for his readers what was won and lost by one man at Shiloh in the spring of 1862.

_____________________________

[1] Bierce, Ambrose. “What I Saw at Shiloh.” The Wasp [San Francisco, CA] December 1881. Print. Retrieved from: http://www.classicreader.com/book/1165/1/ Web. 2 May 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment