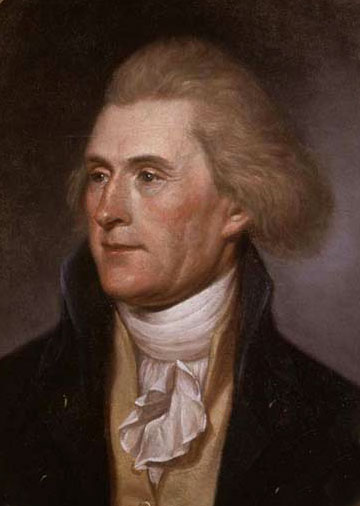

Thomas Jefferson, 1791.

(from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/46/T_Jefferson_by_Charles_Willson_Peale_1791_2.jpg)

In the United States, the 4th of July is celebrated each year as the momentous founding of the country from its revolutionary inception in 1776. The Declaration of Independence, arguably the most hallowed document in the civic religion of America, gave voice to the rebellious colonists who rejected British dominion. Among the arguments the colonists presented for declaring independence was the notion of where governments justly derive their powers. Thomas Jefferson argued in the Declaration that in order to secure the self-evident rights of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” governments specifically derive “…their just powers from the consent of the governed.” “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends,” he concludes, “it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new Government.” Although the argument that all men were created equal was more Enlightenment infused rhetorical flourish than reconcilable reality with the peculiar institution, the 4th of July became a country-wide celebration of the triumph of liberty over political “slavery” to Britain.[1]

Frederick Douglass, circa 1874.

(From George Kendall Warren [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

One person who did not share in this celebration of the 4th of July was Frederick Douglass. Douglass was born into slavery around 1818 in Maryland, and as a young boy was sent to work in the home of Hugh Auld in Baltimore. Douglass, notably, was of a mixed race background, although this was not uncommon or even incompatible with racial slavery in America. The infamous “one-drop” rule was all that needed to qualify as “black.”[2]

Sophia Auld, the wife of Hugh Auld, secretly taught young Frederick the alphabet. An enterprising Douglas continued developing his literacy with white children in his neighborhood and through newspapers like the Colombian Orator.[3] After nearly being psychologically broken working for an abusive “slave-breaker” named Edward Covey, Douglass made up his mind to escape to the northern states. He successfully accomplished this in 1838 with the help of a free black woman named Anna Murray, with whom he later married and settled down with in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where there was already a considerable free black community.

Anne Murray, 1860?

(From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AAnna_Murray-Douglass.jpg)

Soon after, Douglass developed his role as an abolitionist of slavery through his speeches around New England and the publication of his remarkable autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, in 1845. The next two years he spent abroad in Britain avoiding the danger of recapture due to his new found celebrity. It was there where he gave speeches to enthusiastic crowds about the evils of American slavery (Britain had outlawed slavery in 1833). His popularity enabled the purchase of his freedom and the eventual return to America to continue his calls for the abolition of slavery.

It was during time in 1852, at an abolitionist meeting in Rochester, New York, that Douglass gave one of the his most famous speeches. Douglass was asked to speak at a convention commemorating the 4th of July of that year. In the beginning of his speech, Douglass announced: “Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men, too, great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory...”[4]

For what did this noble independence bring to the slave? The idea of a newly minted American government, having successfully wrested power from the British, and being justly conferred power by the “consent” of the governed, sat rather uncomfortably with the reality of slavery. What could Douglass rightfully commemorate or celebrate? Douglass lamented that while there is understandable revelry from free whites of America over the glory of independence, the 4th of July is in fact the opposite to the slave—a time of misery. He explained to his Rochester audience: "Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine."[5]

John Lewis Krimmel's "Fourth of July Celebration in Centre Square, Philadelphia (1819)"

(From John Lewis Krimmel [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Slaves, by not having given consent—either to their masters or their “representative” government—were thus completely excluded from the nation’s republican experiment in liberty and from any celebration of independence. Beyond that, as Douglass needed to point out, the celebration was an insult to the continuing injuries and humiliations of slavery, a time to mourn for those in chains.

So what, Douglass then asked, did the 4th of July really mean to a slave? He provided an answer: "a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to Him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy -- a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour."[6]

As journalist and cultural studies lecturer Gregory Stephens argued, Douglass presented the United States as being imbued with “irreconcilable doubles.” He wrote, “[Douglass’] contrast between July 4 and not-July 4 initiated a radical critique of American citizenship, symbolized by a series of seemingly irreconcilable doubles: white and black, American and not American, free and not free, celebration and mourning.”[7]

Yet, in light his own brutal experiences as a slave, the stark reality of millions of slaves suffering in the United States, and all those seemingly irreconcilable binary contrasts, Douglass was ultimately encouraged by the abolitionist spirit of the age. The destiny of slavery in America, he felt, was at hand. At the close of his speech, he remarked: “...Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery…While drawing encouragement from ‘the Declaration of Independence,’ the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age.”[8]

Douglass would of course live to see the end of slavery in America as part of the series of consequences of the American Civil War that began just nine years later. But on this day, July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass asked his audience to think critically about those American ideas and institutions of independence being celebrated the day before. Douglass’ vision looked beyond the fenced in racial duality of white and black (no doubt influenced by his own multiracialism) and saw a “third space” where the ideal of unity might one day reside. “Even at his most oppositional, as in the July 5 Speech,” Gregory argued, “Douglass affirmed a foundational interrelatedness.”[9] Perhaps it is in this interrelatedness where Douglass foresaw the 4th of July as a celebration by all in the fullest spirit of independence, where all Americans were in principle and in fact free and that their government would have the just consent of all its people. One wonders if Douglass would be cheered on by the obvious tendencies of our current age?

_______________________________________

[1] “Peculiar institution” was a common euphemism for slavery.

[2] Davis, James F. “Who is Black? One Nation’s Definition.” [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/ shows/jefferson/mixed/onedrop.html] Davis wrote, “[the] term "mulatto" was originally used to mean the offspring of a "pure African Negro" and a "pure white." Although the root meaning of mulatto, in Spanish, is "hybrid," "mulatto" came to include the children of unions between whites and so-called "mixed Negroes." For example, Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass, with slave mothers and white fathers, were referred to as mulattoes. To whatever extent their mothers were part white, these men were more than half white. Douglass was evidently part Indian as well, and he looked it.”

[3] http://www.biography.com/people/frederick-douglass-9278324#synopsis

[4] Douglass, Frederick, "The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro." The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Volume II Pre-Civil War Decade 1850-1860. S. Foner, Philip. New York, International Publishers Co., 1950. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2927t.html].

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Stephens, G. (1997). Frederick Douglass' multiracial abolitionism: "antagonistic cooperation" and "redeemable ideas" in the July 5 speech. Communication Studies, 48(3), 175-194. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/233193281?accountid=458

[8] Douglass, Frederick, "The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro." The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Volume II Pre-Civil War Decade 1850-1860. S. Foner, Philip. New York, International Publishers Co., 1950. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2927t.html].

[9] Stephens, G (1997). Frederick Douglass' multiracial abolitionism: "antagonistic cooperation" and "redeemable ideas" in the July 5 speech. Communication Studies, 48(3), 175-194.